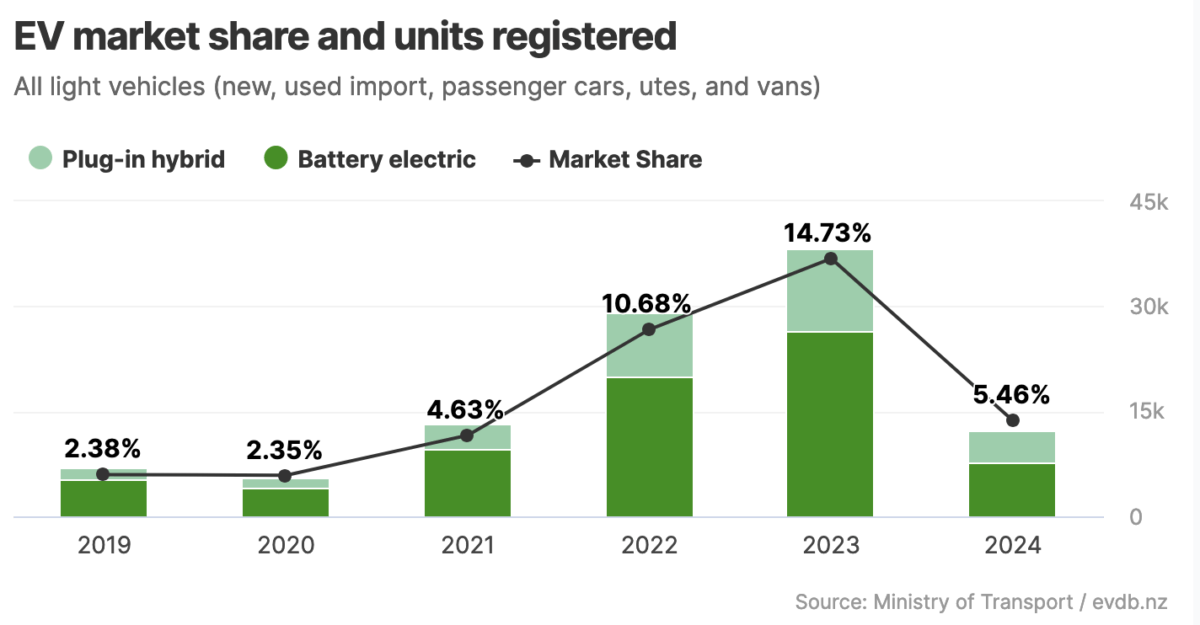

NZ’s recent chaotic EV market share casts a shadow on a predictable transition.

However, global momentum, technological innovation, and charging infrastructure investment suggest the transition is only getting started (albeit slowly).

It was 2016.

We sat at an outdoor table; talking random nonsense.

“Have you heard about EVs?”

“What, like Tesla?” I answered — pretending I had a clue.

“There’s the Nissan Leaf too… and a BMW i-something”.

I asked my friend if he would ever get one. He rubbed his chin, deep in thought.

“When they get 700 km of range—and cheaper, I might get one”.

We had no clues about charging infrastructure or battery longevity, nor the looming spectre of political EV culture wars.

Just a simplistic idea that when a technology reaches a certain point, we buy in.

Crossing the chasm

Penned by Geoffrey Moore in 1991, Crossing the chasm suggests that not all products hit the mainstream. Despite enthusiasm from early adopters, some products fail to ‘cross the chasm’ into the majority (remember the 3D TV?).

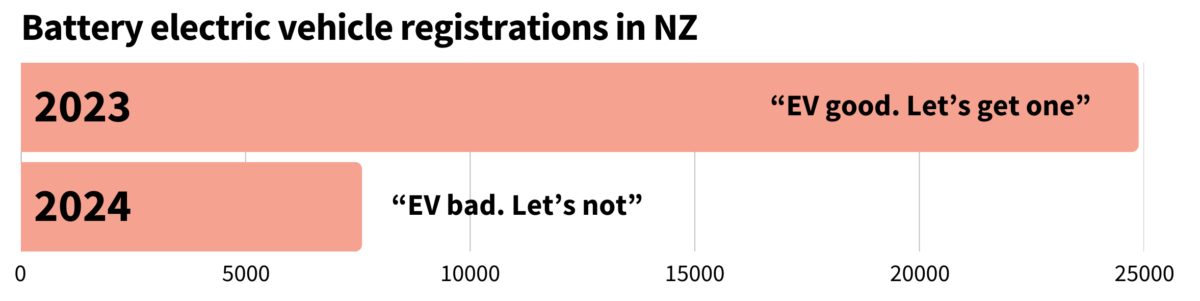

A cursory glance at NZ’s EV uptake (without any context), suggests NZ is struggling to ‘cross the chasm’.

In 2024, EVs were down. But not out.

In the midst of a depressed economy, with a new disincentive for EV ownership (Road User Charges were implemented from April 2024), people still bought EVs.

But given the direction of the graph, some asked: are EVs a passing fad?

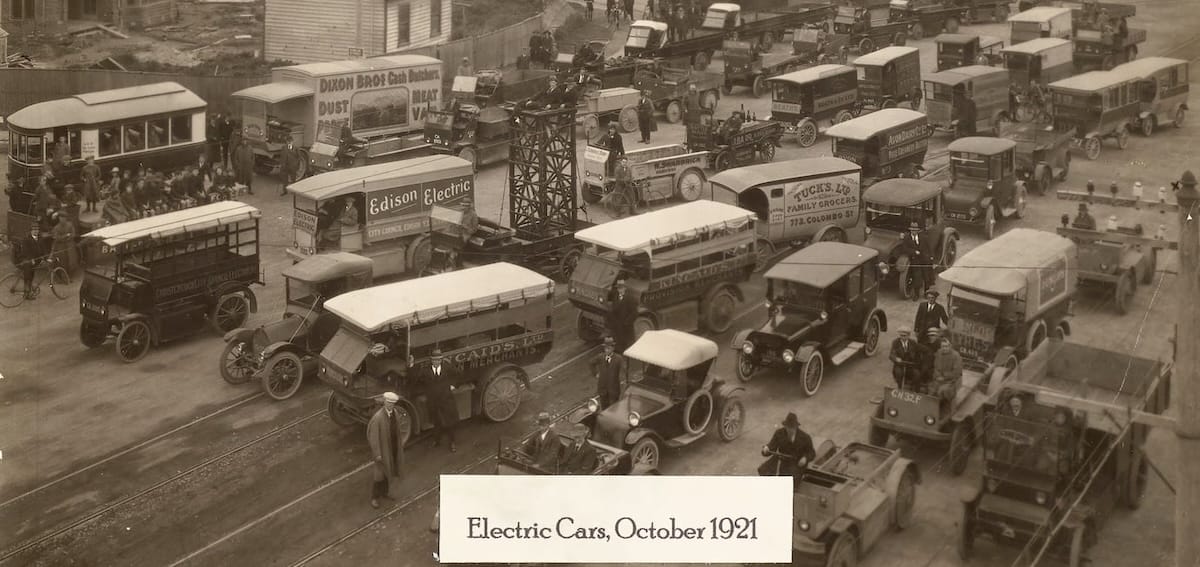

It’s a legitimate question, because it’s happened before.

In the early 1910s electric cars became available.

Even in NZ, as this photo from Christchurch shows. Despite an initial surge of interest, the EV dwindled into obscurity by the 1930s.

Combustion cars became the dominant mode of private transport. It wasn’t just about technology (e.g. energy-dense liquid fuels provided longer range than early battery technology).

US-based research from Nature Energy points to power grid infrastructure:

“We estimate that a 15 or 20 year earlier diffusion of electricity grids would have tipped the balance in favour of electric vehicles, most notably in metropolitan areas.”

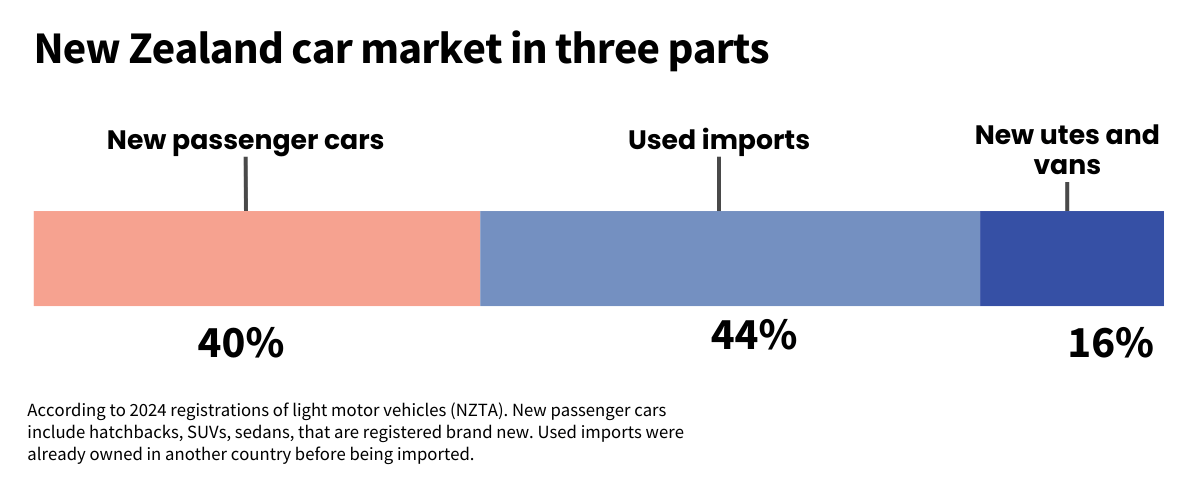

New Zealand has an unusual vehicle market

- We don’t manufacture cars, but only import them.

- We don’t just import new cars; we import lots of secondhand ones.

- We don’t just buy cars, we also buy a fair amount of Utes.

Our car market is dependent on what the rest of the world is doing.

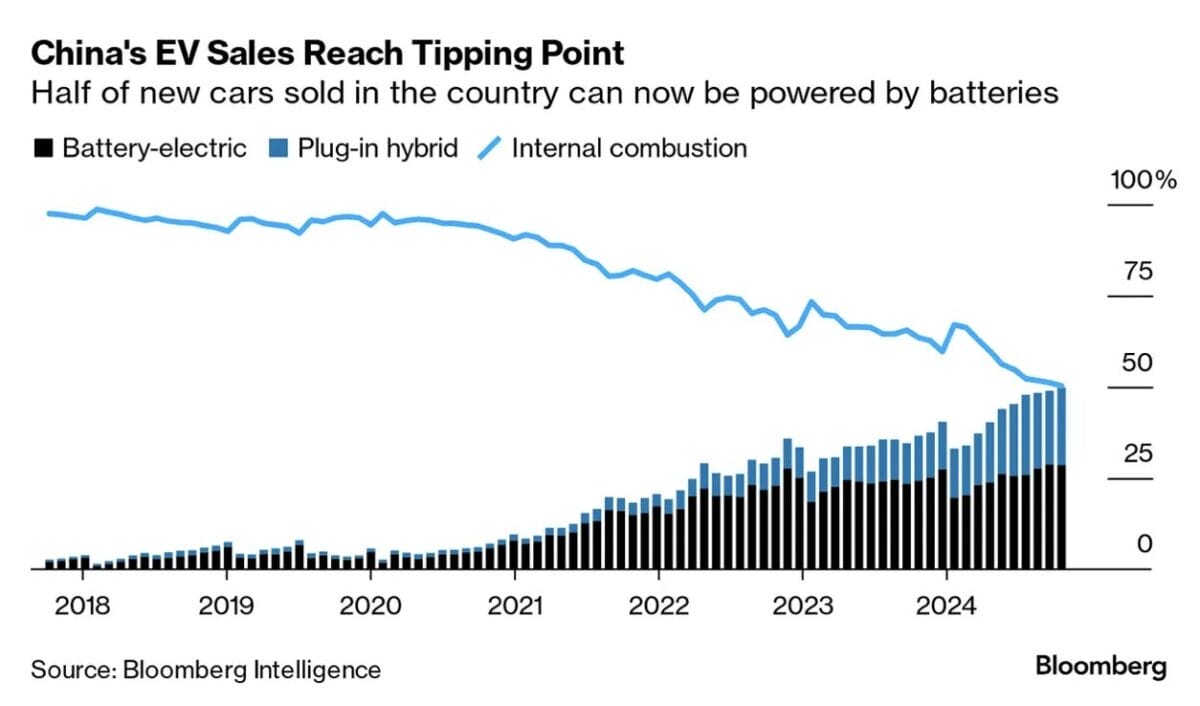

In Norway, the EV transition is almost complete. Other Scandinavian countries also have high EV uptake. The bigger story is China, where EV sales matched combustion sales (50% market share), and are projected to surpass them.

Then, there’s Japan, where pure electric vehicles are a rarity — and hybrid electric-combustion powertrains are seen as the future. Japan also happens to be the country we import most of our used cars from (plus a fair amount of new cars).

There’s a lot going on, and despite NZ’s geographic isolation, we cannot escape global market forces.

What do we want to happen?

Before asking what might happen, we could ask what do we want to happen?

We could opt to stay completely with combustion cars, and live with the status quo:

- We wouldn’t have to change any of our habits (like quick filling up at the petrol pump, or get our heads around the idea of how batteries work).

- Cars might be cheaper (but for how long?)

- We agree to bear the costs of respiratory health (arising from vehicle pollution), along with the obligations the country has from the Paris Agreement. [2]

- We remain content with increasing levels of vehicle noise (particularly in urban areas).

- We are happy purchasing all of our transport energy from overseas companies [1].

Alongside this are broader questions about transport (EV or otherwise):

- Do we want our vehicle fleet to keep on growing (NZ has the highest levels of vehicle ownership in the OECD)?

- Do we value other forms of mobility?

- Do we want to continue shifting to larger vehicles?

The answers to these questions should inform future transport policy – whether EVs are promoted or not. The electric vehicle does not solve transport problems — but it can help reduce emissions, noise, and air pollution. It’s a part of the transport puzzle—a jigsaw made up of efficient mass transit, walkable communities, and bicycles.

Lets learn from those further along the path; Norway’s EV transition resulted in heavier vehicles on the road. But we have an opportunity to shift to small, efficient electric vehicles… as the technology improves.

It doesn’t have to be All or Nothing

NZ’s tiny market is susceptible to big swings in sentiment. Looking at EVs from a binary perspective risks missing some great benefits.

While a fully electric vehicle can be used in all scenarios, it offers superior benefits in certain situations*.

| EV use case | Outcome |

| Second car in a two-car household – the ‘local runner’ | ↑ Lower running costs, minimal behavioural change |

| Only car, mostly local travel. | |

| Lots of regional travel. | |

| Lots of regional travel, and towing | ↓ Higher running costs, more behavioural change |

Running costs and behaviour change?

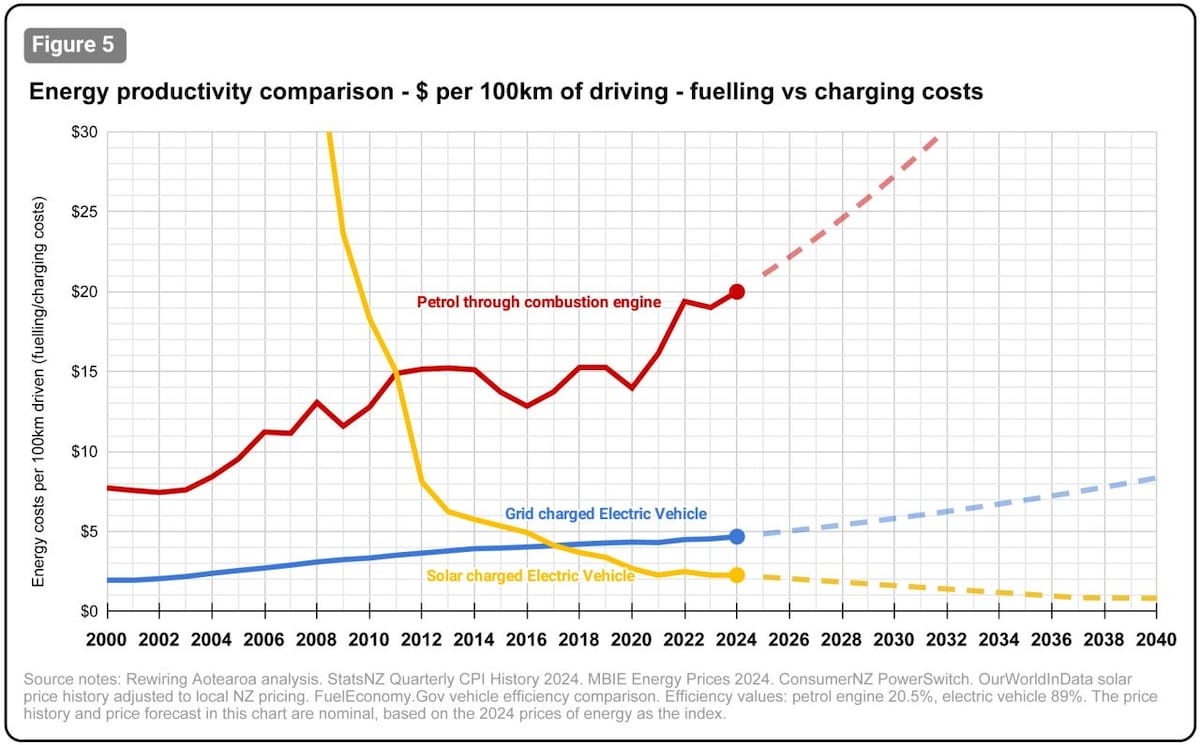

The lowest EV running costs comes from an efficient EV that is primarily charged at home (preferably off-peak). An EV charged from rooftop solar will have the cheapest running costs of any vehicle type.

Behaviour change? Charging at a public DC fast charger is not like filling up at a petrol pump. A mental mode shift is required (e.g. pre-planning, getting used to waiting, etc).

*It’s worth pointing out that EV driving experience (comfort/smoothness/instant torque) can often outweigh all other factors (this is entirely individual and anecdotal).

What will NZ’s future EV uptake look like?

NZ’s light vehicle market can be broken down into three distinct segments. EV uptake is different for each segment.

New passenger cars – EV outlook: growth

- This is where the action is, with foreseeable near-term EV growth.

- NZ will continue to grow market share of hybrid cars. For many, this may be the long-term pathway to battery-electric cars.

- When universal RUC is implemented, attention may return to the running costs of EVs (but only for some) – it’s as much a signalling issue as a cost one; we simply aren’t aware of the road use levy we’re paying when filling up at the pump.

What is a signalling issue?

The messages people hear that inform their choices.

It’s common to hear “you don’t pay RUC on a hybrid car”. While technically true, it’s just that the tax is applied in a different way – hybrids still pay a levy in their petrol.

The oversimplification implies there is one less charge to pay, therefore signals a better choice.

New utes and vans – EV outlook: poor

- The specific demands of a ute (range and towing power) mean a battery-electric form is challenging. A very large battery is required, making it a heavy and expensive vehicle.

- We may first see plug-in hybrids begin to shift the electrification dial. The idea of local electric-only travel plus a portable power supply (vehicle-to-load) is appealing.

- But it’s hard to see the Ute market going EV en masse in the near future. EV vans are available, but often at a price premium.

Used imports – EV outlook: poor

- 90% of our used imports are from Japan.

- 1.6% of car sales in Japan in H12024 were BEVs.

- To add to these small numbers, a number of vehicle shippers are reluctant to ship used EVs from Japan [3].

What will influence long term EV uptake?

Price parity matters

“Prices have got to align to those of internal combustion engines. And to make that happen, you’ve got to be able to offer cars with smaller batteries”

— Andy Palmer in 2024 (former Nissan Leaf engineer – ‘godfather’ of EVs).

During the latter half of 2024, some interesting things happened.

After months of sluggish sales, some importers opted to drastically reduce prices on their EV stock (presumably taking a loss in the process). Models like the Nissan Leaf, Ford Mustang Mach-E, and Volkswagen ID.4 and ID.5 sold hundreds of units only after big discounts.

Demand was there… just not at the existing prices.

Research from FT shows (in the UK) the pricing gap between EVs and combustion cars is around 25%.

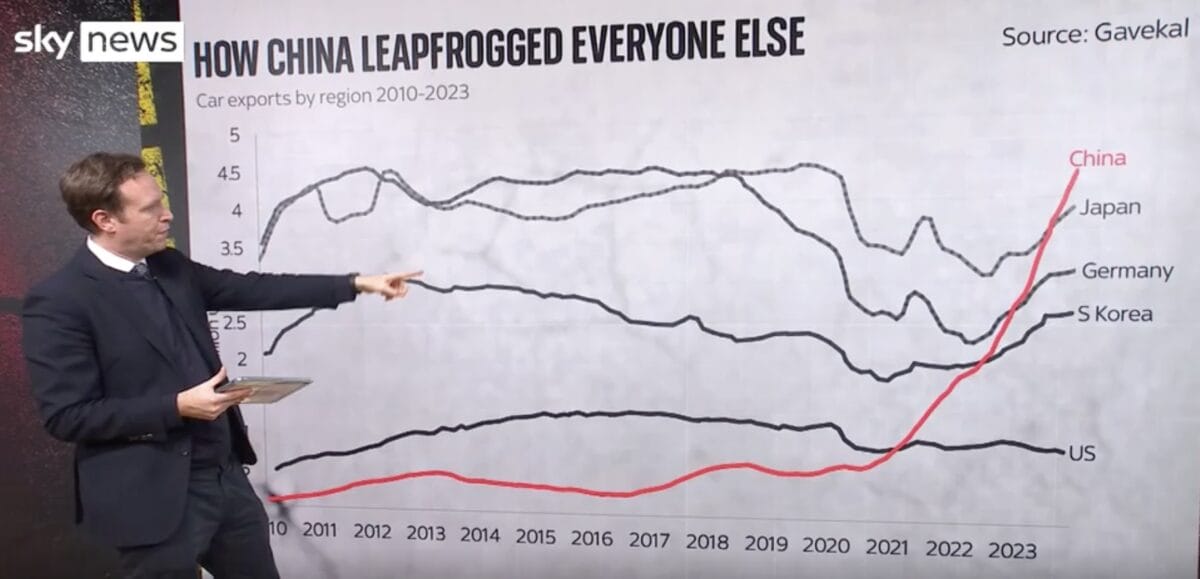

Given that the Chinese car industry is outpacing other exporting nations…

It’s conceivable that Chinese EVs will reach a price point that’s too good to resist (e.g. ever heard anyone say “I’m never gonna buy from Temu… wait, how much is that?”).

But it seems we’re a long way from true price parity.

The batteries: incremental improvement

EV tech has come a long way since the 24 kWh Nissan Leaf battery.

But we also set our expectations high. The mythical solid state battery has been talked up since 2010, but has yet to make it into a mass-production car.

Instead we’re seeing incremental improvement in battery chemistries (NMC and LFP), along with highly sophisticated Battery Management Systems. Energy density is improving and production efficiencies are leading to lower prices.

It’s a long game, yet the innovation trend is visible.

- The 2019 Audi e-tron 55 had a 95 kWh battery, range 441 km (max. charge speed 150 kW).

- The 2025 Audi Q6 e-tron has a 100 kWh battery, range of 625 km (max. charge speed 270 kW)… and the car is ~100 kg lighter.

This same pattern is observed in the upcoming BMW Neue-Klass platform.

To quote independent EV range testers – Norway’s motor.no – “The cars are getting better and better”. [3]

Possibilities: factors that could influence EV uptake

- Future government policy (or lack of)

The feebate scheme (2021-2023) showed how sensitive NZ’s car market is. These changes resulted in ‘chaotic’ monthly car numbers – and a big surge in EV sales. However, even relatively small changes in tone and signalling (from transport policy) could influence buyers. - The price of petrol

When petrol climbs well above $3 per litre people start getting antsy. Some might revisit the idea of EV. - Vehicle efficiency standards

The Clean car standard will impact car pricing at a powertrain level. It’s incumbent on vehicle importers to resist flogging off cheap gas guzzlers – as there’s a cost involved.

Room for improvement: What happens with an all electric fleet?

Electrification brings it’s own set of benefits and challenges. The challenges will need to be addressed:

- Nationwide independent used EV battery testing (and certification).

- A responsible process for collecting, storing, and recycling electric vehicle batteries after their useful lives.

- Resilience and responsibility around charging practices (ensuring grid demand is managed appropriately).

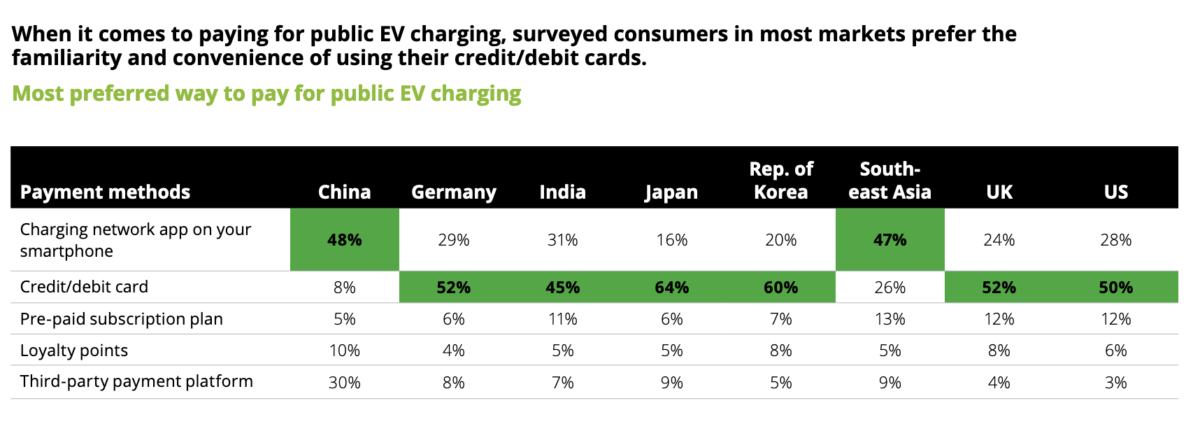

- Significant investment into public charging: allowing credit/debit card payment, ensuring reliability, redundancy, and uptime.

Are EVs a passing fad?

Given the direction of significant parts of the world, along with the investment into NZ’s charging infrastructure — it seems extremely unlikely.

- Tomorrow’s EVs won’t be worse than today’s. They’ll be better.

- Today’s charging infrastructure is at the worst point it will be. It will only improve.

What’s unclear is the time frame.

Cars are not phones. Change takes decades not years.

Countries that have moved faster on EVs tend to have markets dominated by new passenger car sales, and/or have a significantly higher GDP per capita than NZ, or regional mass transit (that is superior to NZ).

This suggests an EV transition that will happen slowly. Why? Because, right now, we can only go electric at the rate we buy new cars.

So, for those who are (or intend to be) new car buyers,

It’s worth reflecting on what we want to happen in the transport sphere…

…before shelling out a significant sum of money for a product that will live on for at least 15 years.

It’s about exercising the power of individual choice to shape the country (and any financial and health burdens) our children will inherit.

Post script:

Did my friend (who wanted the 700 km range) ever buy an EV?

No. His last purchase was a used import hybrid. He admitted it was “gutless” and not much fun to drive, but he could get almost 800 km in between fills.

Is there such a thing as a 700 km range EV?

Yes. The 2025 Polestar 3 Long Range Single Motor. (There’s also the Audi A6).

Endnotes

[1] Fuel cost comparison (from rewiring.nz).

[2] In 2025, the Institute of Actuaries predicted the global economy will face a 50% loss of GDP due to catastrophic climate change (by 2070-2090). They call it ‘Planetary Insolvency’. PDF.

[3] From 2025 winter range test. The median range of an EV in the US reached 283 miles (455 km) at the end of 2024.